Functions & Libraries

A function is a collection of statements that work together to complete a certain task. A function can accept information in the form of arguments/parameters (= input). As a result, it can return data (= output).

R includes a vast variety of built-in functions, and users can write their own.

Call a Function

You've already learnt how to call functions unintentionally in previous chapters.

In the following, we will use the sd() function to demonstrate how to call a function.

It is utilized to calculate the standard deviation.

Type the name of the function followed by parentheses, such as sd(), and the arguments between the parentheses (arguments are separated by a comma):

# Calculate the standard deviation of 2, 4, 5 and 8

sd(c(2, 4, 5, 8))

output:

[1] 2.5

Variables can also be used as function arguments:

values <- c(2, 4, 5, 8)

sd(values)

output:

[1] 2.5

You may also assign the function's output to a variable if you wish to reuse the function's output:

my_sd <- sd(values)

my_sd

output:

[1] 2.5

Built-in Functions

Basic examples of built-in functions are seq(), mean(), max(), sum(), and paste(), among others.

Function Information

With help() or ?, you can receive information about a function:

# Find out information about sd()

help(sd)

?sd

With args(), you can simply call the arguments of the function:

# Call the arguments of sd()

args(sd)

output:

function (x, na.rm = FALSE)

NULL

Argument Matching

The description for sd() shows that the function actually takes two arguments: sd(x, na.rm = FALSE).

When you enter sd(values) into the R console, R understands that values is the argument x and not na.rm.

That is because of the arguments' positioning (values comes first, such as x).

Another way to match the arguments is by using the equal sign: sd(x = values).

Default Values

The second argument to the sd() function indicates that by default na.rm is set to FALSE (even if you do not specify this argument yourself).

This means that missing values will not be eliminated.

However, default values can be overwritten, e.g. na.rm = TRUE.

In contrast, x is not specified by default.

If you do not specify the value of an argument without default values, an error will occur.

Nested Functions

R allows you to use functions within functions.

To get the absolute difference of two vectors you can nest abs() and mean():

# example vector, containing patient age data

gynaecology <- c(16, 49, 25, 20, 33, 56)

dermatology <- c(77, 56, 16, 28, 43, 64)

# Calculate the mean absolute difference

mean(abs(gynaecology - dermatology))

output:

[1] 17.16667

User-Defined Functions

Create a Function

You can define custom functions via the following syntax:

function_name <- function(arguments) {

body

}

- Function name: It should be short yet clear and meaningful, so that the person who sees our code understands exactly what this function performs.

- Function arguments: We have already covered what arguments are. But it is possible for a function to have no arguments, although this is rarely practical. You can have as many arguments as you like, and you may assign default values to them.

- Function body: The function body is a collection of commands enclosed by curly braces that are executed in a preset sequence each time the function is called.

We want to create a function that squares the given integer.

# Build the function square()

square <- function(x) {

x^2

}

# Calculate 4 squared

square(4)

output:

[1] 16

Return Values

By default, R returns the value of the function's final statement.

However, you may use the return() function to directly tell R what to return.

We want to create a function that squares the given integer.

# Return the value y by assigning y to x squared

square <- function(x) {

y = x^2

return(y)

}

# Calculate 4 squared

square(4)

output:

[1] 16

Function Scoping

In the scope of on R function variables outside the function are not accessible.

Consider our global R environment (our whole program) to be a room that contains all the objects, variables, functions, etc. that we have utilized. When we call a variable x, R will search around the room to get the value of x.

We may use ls() to see what's in our environment.

As we define a new function, R sets up a fresh temporary environment for it. Imagine setting up a new room within our global R environment. The new room contains all the objects we have created, modified, and used within the function. But, as soon as the function is finished performing, the room disappears.

The next example will show you that the variable txt does not exist outside the function, only inside it.

# Create a function with a local variable

R <- function() {

txt <- "cool"

paste("R is", txt)

}

# Print out R()

R()

output:

[1] "R is cool"

# Call the variable txt

txt

output:

Error: object 'txt' not found

You may use the global assignment operator <<- to define a global variable inside a function.

# Create a function with a global variable

R <- function() {

txt <<- "cool"

paste("R is", txt)

}

# Print out R()

R()

output:

[1] "R is cool"

# Call the variable txt

txt

output:

[1] "cool"

The variable txt is now accessible outside the function.

R Packages

R packages are accessible collections of data, code, and documentation and are essentially additions or extensions to the R software.

R already offers built-in packages, such as the base package, which includes functions such as mean(), list(), and sample() among others.

However, for more in-depth data analysis, you might want to use more than that.

Install and Load Packages

You can use R's built-in install.packages() function to install packages on your computer's hard drive.

This function navigates to CRAN (Comprehensive R Archive Network), a repository containing thousands of packages, and downloads them.

Afterwards, you have to load the package into memory by using library().

This enables usage of a package's functionality throughout the current R session.

Therefore, before beginning a new R session, you must always load all the packages you intend to use.

Alternatively, you could call the require() function, which works similarly.

# Install the ggplot2 package

install.packages("ggplot2")

# Load the ggplot2 package

library(ggplot2)

Identify Loaded Packages

If we want to see which packages we loaded, we may go to the packages tab in the console's bottom right window. We may search for packages and load them by ticking the box next to them.

You could also enter (.packages()) or search() into the console.

They will display all the packages that are currently loaded into memory.

(.packages())

output:

[1] "ggplot2" "stats" "graphics" "grDevices" "utils" "datasets" "methods" "base"

search()

output:

[1] ".GlobalEnv" "package:ggplot2" "tools:rstudio" "package:stats" "package:graphics"

[6] "package:grDevices" "package:utils" "package:datasets" "package:methods" "Autoloads"

[11] "package:base"

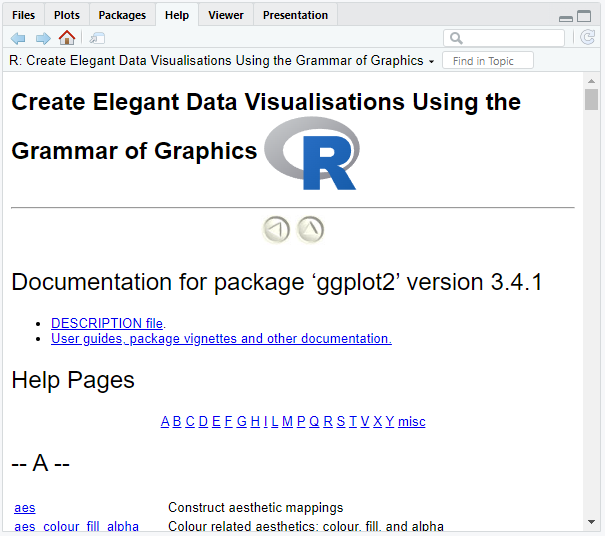

Package Information

By clicking the package name in the packages tab, we may get additional information about the selected package in the help tab.

If we click the ggplot2 package, we get the following:

Alternatively, we may type help(package = "ggplot2") into the R console. This will also lead you to the help tab.